The view from King Philip Mountain along the Metacomet Trail at Talcott Mountain State Park

My introduction to King Philip came in the fall of 2022 while hiking the Metacomet Trail at Talcott Mountain State Park. I noticed a landmark on AllTrails called “King Philip’s Cave”. That sounded interesting! The trail was unmarked, but with my GPS, we found ourselves on a narrow path below a vertical cliff looking up at the mouth of a cave. But who was this King Philip and why was there a cave named after him? I found this intriguing tidbit on the Town of Simsbury’s website: “In 1676 [sic], Indian disputes erupted into King Philip’s War, and in March Simsbury was attacked by a group of Philip’s warriors and burned to the ground. According to legend, their leader, King Philip, sat in the large cave on Talcott Mountain to view the spectacle. It is still called the Metacomet Ridge.” (King Philip was the great sachem of the Wampanoag people and his Algonquian name was Metacom. More on that later.) What a great tale! I could picture him in my mind, sitting cross-legged under the overhang, stoically watching the small settlement burn, a look of grim satisfaction on his face. This sent me down yet another rabbit hole, reading books and articles, listening to podcasts, and imagining a Trail Talk post where I followed King Philip’s route. Then things got complicated. The more I researched, the more I learned that the war involved not just King Philip’s tribe, but other Algonquian allies across New England. And then, while reading Michael Leroy Oberg’s book, “Uncas: First of the Mohegans”, I came upon this passage: “Events in late March 1676 underscored the urgency of launching a campaign against the Narragansett. On the 26th, Narragansett warriors attacked and destroyed the village of Simsbury in eastern Connecticut”. Say, WHAT?

How was I going to follow in King Philip’s footsteps if he wasn’t even there? (I have since read in other places that this legend is almost certainly apocryphal, including a statement by the former Connecticut State Archaeologist, Nicholas Bellatoni). Then I thought about the 62-mile blue-blazed Metacomet Trail that runs from Meriden to the Massachusetts border and decided to pivot; instead of following in King Philip’s literal footsteps, I would write about the Metacomet Trail, King Philip’s Cave, and all the places he (probably) never was.

While this may sound flippant, it isn’t intended to be. My deep dive taught me so much about this pivotal time in our nation’s history. While we get ready to celebrate America 250 next year, let’s pause to ponder the events that took place 350 years ago that left an indelible mark on the course of our history. The irony of the trail name is that it passes through areas that were populated by other Algonquian language family tribes (likely some Wangunk, Poquonock, Pocumtuck and others) many of whom tried to stay neutral during the war. No matter how these tribes approached the war, they were all affected by it, and in the war’s aftermath often forced to sell their land, flee or be sold into slavery.

The overlook on the steep cliff face above King Philip’s Cave

A Brief History

This is a trails blog, not a history blog. I will do my best to summarize what I have learned, but it gets complicated and I will inevitably leave a lot out. Please visit my Bibliography at the end of this post, where I share my resources so you, too, can take a deeper dive. Please forgive any errors and omissions.

In 1675 the Indians and the English inhabiting this area had been living in proximity to one another for over 50 years, but they were not merely two groups. In his book “War of the Lords”, Matthew J. Tuininga shows a chart of Indian Communities listing at least 10 different groups or “confederacies” made up of over 75 different tribes. The New England towns were governed under four distinct colonies. Three of them – Plymouth, Massachusetts Bay, and Connecticut Colony – had officially united in 1643 as the New England Confederation and had a mutual aid agreement. The colony of Rhode Island was not part of the confederation. There were also fourteen “Praying Towns” where somewhere between 1,000 and 2,000 converted Christian Indians lived.

Over the course of those 50+ years these communities (Indian and English), so distinct from each other in most respects, generally found ways to co-exist without violence, one exception being the Pequot War in 1637-38 which I wrote about in this TRAIL TALK post. Several factors made this possible early on: Massasoit Ousemequin,the Great Sachem of the Wampanoag confederacy and King Philip’s father, welcomed the pilgrims after they arrived on the shores of what is now Plymouth in 1620. The Wampanoag and other coastal Indians had been devastated by disease, losing as much as 90% of their people, and it’s probable that Massasoit viewed an alliance with these settlers as protection against their neighboring rivals the Narragansett, who had not been so devastated. Another factor was that the populations were relatively small to start – the Indian population having been reduced drastically by disease between 1616 and 1619, and the English population, at least early on, had not yet exploded, although by 1675 it had swelled to around 65,000. Another factor was a mutual interest in trade, with the Indians coveting metal goods, cloth and clothing, glass beads, alcohol, guns and ammunition, and the English coveting furs, food, wampum (used as currency before coinage) and, most crucially, land.

The Indians and the English viewed land differently. For Indian communities land was a shared resource with established rights for planting and hunting. Many Indian villages moved seasonally, and there was no concept of permanent ownership. They also had a spiritual connection to the land, often viewing the landscape as animate. The English viewed the taming and “improving” of land as critical to survival. For them, land was something that could be bought or sold and permanently owned, once improved upon, with hereditable rights. As more and more land deals took place, tensions and conflicts mounted, perhaps due to a combination of misunderstandings of land use, intentional obfuscation on the part of the English in negotiating deals, a reliance on translators, forcing debt situations that then required deeding away land as repayment, and non-compliance (one Indian complaint was English cattle being allowed to roam and destroy crops).

Before his death around 1661, Massasoit urged his sons Wamsetta and Metacom to petition the Plymouth court for English names. (It was an Algonquian custom to adopt a new name upon certain life events.) Wamsetta became Alexander, and Metacom became Philip, seemingly in reference to the Macedonians in the Bible. Alexander, the elder brother, was sachem until his untimely death in 1662 (there were well-founded rumors that he was poisoned) and he was succeeded by Philip as sachem of the Pokanoket tribe and Great Sachem of the Wampanoag people. While historians disagree about whether they requested English names or were pressured to take them, and whether or not “King” was the appropriate moniker, Philip himself continued throughout his life to sign his name as King Philip.

Tensions continued to grow over the next decade until they reached a tipping point. Historians often point to the death of John Sassamon in the winter of 1675, and the subsequent trial and hanging of the three accused of his murder, as the catalyst for the war. Sassamon was a Christian Indian who straddled two worlds and perhaps played them both to his advantage. He was the protégée of John Eliot, a Puritan missionary whose life’s work was evangelizing Indians. It was Eliot who envisioned the Praying Towns, establishing the first one in Natick with the help of Sassamon, who became a schoolmaster there. In intervening years Sassamon left to live with the Wampanoag and act in some capacity on King Philip’s behalf (he is often recorded as a witness to legal documents). The impetus for his movements is unknown, but include the possibility of being tasked with converting King Philip (something Eliot keenly wanted to do) or to act as a spy for the colonists. Sassamon disappeared in January of 1675 sometime after he secretly warned Plymouth Colony Governor Josiah Winslow that Philip was preparing for war. His body was found in a pond in February and three Wampanoag from Philip’s inner circle were accused of his murder. Rather than allow the tribe to adjudicate, Plymouth Colony insisted on holding trial. The accused were found guilty and hanged on June 8, 1675, and two weeks later Philip’s warriors raided the town of Swansea, killing nine colonists. At first, the conflict was between the Pokanoket and Plymouth Colony, but as fighting continued, Massachusetts and Connecticut joined the war on Plymouth’s side, and numerous tribes from several confederacies joined King Philip, including most Wampanoag and Nipmuc tribes. The Narragansett originally tried to stay neutral, but eventually joined the conflict on King Philip’s side. Rhode Island stayed neutral, but suffered the effects of the war, including the burning of Providence. The Mohegan tribe allied with the English, as they had in the Pequot War, and so did a number of the Praying Indians, although sadly this did not save them from much distrust and later internment on Deer Island (reminiscent of the US treatment of Japanese-Americans during WWII).

The war spread across all of Massachusetts and into Rhode Island, and as far north as New Hampshire and Maine (then part of Massachusetts Colony). Aside from the burning of Simsbury, Connecticut towns mostly came out unscathed. One of the turning points in the war was the utilization of Christian Indian scouts, which the English attributed to them being good Christians who wanted to defeat the enemy. However, Lisa Brooks points out in her book, Our Beloved Kin: A New History of King Philip’s War: “[s]ome regarded service as a forced obligation, following months of exposure and starvation [on Deer Island]. Many were also motivated by the responsibilities for the survival of their kin.”

On August 12, 1676 near Mount Hope (present-day Bristol, RI), King Philip was shot and killed by a Wampanoag Christian Indian who was fighting with the English under the leadership of Benjamin Church. This essentially ended the war, according to the English narrative,but skirmishes continued in northern New England for a long time. Lisa Brooks writes: “The conflict that began in Metacom’s homeland continued long beyond his death, perhaps for another hundred years. Or as some would say, perhaps that war has never ended at all.” In fourteen months of fighting about 4-5% of the English population (2,500 people) were killed, the highest death toll per capita of any American war, and out of approximately 90 towns and villages, 60% were attacked and 10-20% burned to the ground. Native American losses were even more devastating. Of the estimated 20,000-25,000 Indian population in southern New England at the start of the war approximately 5,000 were killed and 2,000 sold into slavery, primarily to the West Indies. Despite these losses, the population was not extirpated. Some surrendered, fled north, escaped from enslavement, or intermarried. Over the centuries, by maintaining small, tight-knit communities and preserving oral traditions, these descendants fought for their rights and for land. Today, along with the Mohegan and Mashantucket Pequot, the Mashpee Wampanoag, the Wampanoag Tribe of Gay Head (Aquinnah) and the Narragansett Tribe are all federally recognized. (See the Bibliography for more information).

There is SO much more to the story of King Philip’s War, but no more room to tell it here. As you hike the Metacomet Trail, which goes along the Metacomet Ridge, I encourage you to think of all this rich history, and of the people who may (or may not) have walked these paths before you.

The Metacomet Trail

Along the Metacomet Trail in the Hanging Hills of Meriden

The first sections of the Metacomet Trail, in the area of the Hanging Hills of Meriden, were built in the 1930’s by the Connecticut Forest and Park Association (CFPA). Today, this 62 mile trail runs from Meriden to the Massachusetts border, and has been incorporated into the 235 mile New England National Scenic Trail (NET) that was officially designated in 2009. The NET runs from the Connecticut shore to the Canadian border. The Metacomet Trail goes along trap rock ridges, formed over the millennia by erosion around ancient lava flows. Trap rock is the generic term for basalt or diabase volcanic rock, and comes from the Swedish word “trappa”, meaning “step”, because of the way the rock formations often resemble stairs. This landscape creates microclimates that are unique to the area which support rare flora and fauna not found elsewhere in Connecticut (see Trap Rock Ridges of Connecticut: Natural History and Land Use for a full explanation of these unique environments). As such, most of the trails I describe are rated moderate-to-difficult for their elevation changes and rocky footing. There are a few places, such as Castle Craig, where you can experience a section of the trail more easily.

I have not hiked all 62 miles. Some of those miles are road walks connecting sections of woodland trail. Following is information, organized from south to north, of the trail sections I have explored. The Metacomet Trail starts in Berlin along Route 5 where it connects to the northern terminus of the Mattabesett Trail to the east. The trail heads southwest across the Hanging Hills into Meriden, and once it reaches Hubbard Park it loops north.

Hubbard Park – Castle Craig, East Peak and West Peak, Meriden. 3.5+ miles

“And if a man shall meet the Black Dog once it shall be for joy; and if twice, it shall be for sorrow; and the third time he shall die.”

That is the opening line of the gothic tale “The Black Dog”, by W. H. C. Pynchon, published in the April-June 1898 issue of The Connecticut Quarterly. The setting is the Hanging Hills of Meriden – one of Connecticut’s storied trap rock ridges. The opening paragraph reads: “In a corner of our country not far removed from two of its great cities, there is a low range of mountains, the hoary evidences of ancient volcanic action. Countless years have elapsed since the great tide of molten lava rolled over the region.” Perhaps because Pynchon was himself a Harvard educated geologist (just like the story’s narrator), the story took on a life of its own, becoming a famous Connecticut legend, and is often referred to as a “true” tale. I first visited the Hanging Hills for a sunrise hike in October of 2021 just in time for Halloween. My plan was to do a clockwise loop hike from Mirror Lake. Click HERE for the Trail Map.

On that first visit I failed to follow my own advice, which is to always scope out a trail before attempting a sunrise hike, as it is always harder to find your way in the dark. Fortunately, with the help of AllTrails, I managed to find the pedestrian bridge that crosses Highway 691. Following the white, then red trail, I eventually reached the blue-blazed Metacomet Trail. The blue trail to the left leads to West Peak. I followed the blue trail to the right, as it climbed steeply north up a rocky incline. The trail turns right just before reaching Peak Road and follows an eastward path with several scenic vistas to the south before reaching Castle Craig. The castle was built for and given to the people of Meriden in 1900 by Walter Hubbard, President of the Bradley and Hubbard Manufacturing Company and for whom the park is named.

From left to right: the castle at sunrise; the pedestrian bridge over I-691; the stairs to climb to the castle turret; southern skies from a viewpoint at sunrise

NOTE: The gates are open to drive up to Castle Craig from May 1 to October 31 from 10:00am to 4:45pm. This is a good way to experience the Metacomet Trail and the trap rock ridges without a difficult hike.

From the castle parking lot, the blue trail continues east and the orange trail drops steeply downhill to the south (the SCRCOG Trail Map depicts this as a white trail, as does the Meriden Land Trust map. I found another Trail Map from the “Scenes From the Trail” blog that I believe shows it correctly.) I took the orange trail to meet the white trail, heading east (left) then followed the yellow trail to the Merimere Reservoir before making my way back to the parking lot. AllTrails is useful at this point to avoid as much of a road walk as possible. I recorded this loop as 3.55 miles.

From left to right: Heading down the orange trail from the castle; a classic trap rock “step” configuration; the Merimere Reservoir; typical trap rock scene.

The next October a friend and I followed the same loop but added an out-and-back to West Peak. The trail to West Peak is steep with a vertiginous slope that drops away. There are nice views at the top, although the peak is dominated by communications towers. I recorded 4.75 miles.

Last October I did the loop again, but after the castle I stayed on the blue-blazed Metacomet Trail heading eastward until I came to the vistas overlooking the Merimere Reservoir and Mine Island. Then I backtracked and finished the loop as before for a total of 4.2 miles.

From left to right: the West Peak slope; West Peak view; Merimere Reservoir from above; typical trail section

Ragged Mountain Preserve, Berlin. 4.5 to 6.25 miles

The Metacomet Trail passes over Ragged Mountain, which is a fun hiking destination because there are many options for loop hikes of varying distances. For the Trail Map click HERE. There is limited parking along West Lane in Berlin. Whereas I have always visited Hubbard Park in October, February is my go-to month for Ragged Mountain, so I have only experienced these trails in the snow, which presents its own set of challenges. On my first visit in 2021, we did a counterclockwise loop of the perimeter trails for a total of 6.25 miles. We started north on the red/blue trail where we soon encountered our first challenge: crossing a wide stream by walking across a log. Hiking poles and microspikes were necessities on this hike. After circling the north end of the ridge the trail intersects with the blue-blazed Metacomet Trail. Stay straight/left to head south along the ridge where there are scenic views of the Wassel Reservoir. When you reach the southern end of the preserve, watch for the red/blue trail on the left to complete the loop to the trailhead. There are great views of Hart Pond from the eastern side of the preserve.

I visited again for a solo hike in February of 2024, this time going clockwise, following the red/blue trail south to its intersection with the blue-blazed Metacomet Trail, then heading north on blue until I reached the yellow/blue cross trail. This took me back to the red/blue trail and trailhead for a total distance of 4.5 miles with 950’ of ascent. There are at least four trails that connect the blue and red/blue trails so there are many options.

From left to right: Me crossing the stream; view of the Wassel Reservoir; typical trap rock landscape; view of Hart Pond

Bradley Mountain and Crescent Lake Loop, Southington. 3 miles

This moderate loop trail includes a portion of the Metacomet Trail that lies between Ragged Mountain and Pinnacle Rock. There is ample parking at Crescent Lake, which is open to the public for fishing. There are a few scattered picnic tables and benches and a portalet. We followed this AllTrails map, but it is also useful to look at this Town Map which shows the different trail blaze colors, although there have been some additions since it was created.

MAP NOTES: The red trail goes along the edges of the lake; the orange trail appears more gold on the map; there is a light green blazed trail that we took back after doing a short out-and-back to Bradley Mountain. This trail shows in AllTrails but not on the town map.

From the parking lot, the red and the blue/orange trails start out together. We followed the red trail to go along the lake. If you do this, pay attention and take the short unmarked trail at the southeast corner of the lake to connect back with the blue/orange trail. Stay on blue/orange as it climbs a rocky road. As the ground starts to level out, look for the junction with the blue Metacomet trail. Turn left, and follow the ridge to a wide expanse of rock with a view of the lake. This section of trail is also blazed orange. This is the “Sunset Rock” from which the now defunct Sunset Rock State Park got its name. I imagine it is an amazing sunset spot, but be advised there is a sign at the parking lot kiosk stating that the parking lot closes at dusk and to “Obey Closing Times or You May Be Locked In!”

From left to right: Along Crescent Lake; junction with the Metacomet Trail; the trap rock cliff; view from Sunset Rock with haze from the Canada wildfires

We continued along the ridge and stayed on blue where the orange trail descended on the left. At the next junction the blue trail goes right. We went left to take the blue/red blazed trail. After a while we noted another trail on the left, this one blazed light green. This would be the one we would connect to later. We continued on blue/red a short distance to reach the summit of Bradley Mountain. The views should be better when the leaves come down. From there we retraced our steps to the light green trail. This was a much easier section of trail which descended through a woodland, meeting up with the orange trail before reaching the lake. At the lake, access to the dam is prohibited, so there is a short road walk to get back to the parking lot. For more information about Crescent Lake, the trails and bow hunting season click HERE.

From left to right: Ascending Bradley Mountain Summit; view from Bradley Mountain; the new “light green” trail; a section of boardwalk through the woods

Pinnacle Rock/Rattlesnake Mountain/Hill-Stead Museum

With two vehicles you can do a point-to-point hike of approximately 6 miles. I did this section as 3 separate out-and-back hikes in July. My first introduction to Rattlesnake Mountain was a sunrise hike in November of 2021. The 1.3 miles to the lookout didn’t seem overly strenuous and the sunrise was spectacular. Fast forward to July of 2025. My friend and I repeated this hike and extended it another mile to reach Pinnacle Rock in Plainville for a total of 4.6 miles roundtrip. I wither in the heat, and this hike kicked my butt. The parking area is a pullout on Route 6 in Farmington, so use caution pulling in and out. We didn’t have any problem finding a spot on a weekday morning. There is a short side trail blazed blue/white that leads to the main blue-blazed Metacomet Trail. At this junction, go right and continue along a well-maintained, easy section of trail that includes many features built by CFPA volunteers including bog bridging, gravel and railroad tie steps and rock stairs. After a half mile or so the trail goes past some impressive rock faces. At the 1.2 mile mark at a 90 degree turn in the trail look for Will Warren’s Den, marked by a bronze plaque. According to the CFPA Walk Book, legend has it that in the 1600’s, Warren “tried to burn down the village of Farmington after he was flogged for not going to church. Driven out of town and pursued into the mountains, he was hidden in this cave by Native American maidens.” At the 1.3 mile mark we took a welcome break on the rocky cliff overlook on Rattlesnake Mountain.

From left to right: Rattlesnake Mountain at sunrise; CFPA built steps; Will Warren’s Den; Rattlesnake Mountain in summer

The next mile was more challenging. The trail drops and follows a steep, rocky section along the base of the cliff, at one point passing through a cave-like opening. Upon reaching the ravine floor the trail became overgrown as we crossed the power line corridor. The trail continues up the other side of the ravine. At one point we had the option to take a blue/red cliff bypass trail to avoid a steep descent down a rocky cliff. We opted to take the cliff path down and the bypass on the way up. We were thrilled to finally arrive at Pinnacle Rock, which is a large rocky outcropping marked by a squat stone pillar.

From left to right: Descending off the back of Rattlesnake Mountain; the overgrown power line section; view of Rattlesnake Mountain from Pinnacle Rock; Pinnacle Rock

A few days later I planned an early hike to Pinnacle Rock from the Plainville side – 3.6 miles roundtrip with 783’ of total ascent. The trailhead is on Route 372 and you have to park across the street in the New Britain Medical Building lot. The trail is rocky as it heads uphill to the ridge, skirting the Tilcon quarry and running parallel to Route 372. As the trail moves away from the road the noise lessens. Traversing the ridge I imagine there are good views seasonally. The trail undulates as it climbs to Pinnacle Rock, passing the occasional viewpoint. About ¼ mile before the top the trail goes past the remains of an old missile site. There is a concrete base along the trail, and much wire fencing. From the top there are great views of Rattlesnake Mountain.

From left to right: the trailhead at Rt. 372; a typical section of trail; the view of Pinnacle Rock with Rattlesnake Mountain in the distance; view from the top

A few days later I did another early out and back, parking on Route 6 again, and heading northeast above the Farmington Reservoir to the Hill-Stead Museum. The sketchiest part of this hike is the road crossing to reach the trailhead. It is easy to miss the trail start. Once you enter the woods, the trail take a sharp right going steeply uphill. Don’t take the more obvious path behind the trail sign. This is a generally easy trail, undulating with gentle elevation changes. At the beginning as you traverse the ridge there is an occasional view, and I imagine there are decent views of the reservoir once the leaves come down. Just before reaching Route 4 watch for a junction with an obvious trail on the left. This is the Woodland Trail on the Hill-Stead Museum grounds. With the help of AllTrails, I followed some of the museum trails to reach the parking lot and stopped at the picnic table by the kiosk for a drink and a snack. I made this my turnaround point as I knew the temperatures were climbing. If you have time, I have heard that the museum gardens are lovely and worth a stroll. I recorded 4.35 miles with 605’ of ascent.

The Hill-Stead grounds and hiking trails are open to the public daily from 7:30am to 5:30pm. There is a map on the kiosk by the parking lot. If you visit during the museum’s open hours (Wednesday through Sunday 10-4) you can take a house tour and/or visit the museum. Check the website for details and to purchase tickets in advance. https://hillstead.org/

From left to right: Hazy view from the ridge; boulder along the trail; Hill-Stead museum trails

Talcott Mountain State Park. 5 to 6 miles

This was the trail that started it all. First a note on the name Talcott. I read in several places that Talcott Mountain is named after a Revolutionary War hero named John Talcott. I queried ChatGPT for details, and got that same origin story, along with this tantalizing tidbit: “This John Talcott may refer to a descendant of the colonial John Talcott who served in the Connecticut militia during King Philip’s War.” I pushed ChatGPT harder, this time asking for sources, and it finally coughed up this: “No documentation surfaces for a Revolutionary War soldier of that name from Connecticut, nor for actions during the period that would explain naming a mountain after him.” My interpretation? It seems more likely that the mountain was named either for the John Talcott who led Connecticut forces in King Philip’s War, or his son, Joseph Talcott, who served as a Governor of Connecticut Colony from 1725 to 1742.

On that first visit, we parked in the Penwood State Park lot and crossed Route 185 to walk up the paved road into Talcott Mountain State Park. Click HERE for the Trail Map. We turned left on the gravel road (blazed in yellow) at the sign for the Heublein Tower. When you near the ridge, the gravel road takes a sharp left turn; stay straight here on an unmarked trail to reach a scenic overlook. There is a red sign on a tree reading “Rescue Access 2”. At this spot you are above the cave. To locate the cave, we used AllTrails to guide us north until we reached a trail where we could circle back below the ledge. The trails are unmarked and follow along a steep drop-off. The first cave we encountered was not too high up, but it turns out this was a decoy. The real cave was further along the path and very high up. The path is a bit treacherous, so I don’t recommend doing it unless you are experienced navigating difficult terrain. I definitely recommend against trying to access the cave. It was enough for me to gaze at it from below. From there we retraced our steps to the yellow trail and followed it south to the Heublein Tower. The Heublein Tower is an historic home and museum that is open seasonally (I have never visited it). For more information, click HERE. NOTE: Hiking poles are not allowed inside. From the tower, we took the blue-blazed Metacomet Trail south and east to Hartford Reservoir Number 6. We explored along the Reservoir before heading north on the red/blue blazed trail where it eventually joined the blue blazed trail, which we took east (right) to take us back to the parking lot. That loop was a little over 6 miles. NOTE: Either coming or going I recommend driving along Nod Road which runs parallel to the park on the western side. You will have great views of the ridgeline and the tower.

From left to right: November view from the ridge; this “Rescue Access 2” sign appears above King Philip’s Cave and also below along the unmarked access trail; view of the cave from below; the Heublein Tower

My husband joined me in May of this year and we did a different loop, recording 5 miles and 942’ of ascent. This time we started on the blue-blazed Metacomet Trail directly across from the Penwood State Park parking lot. As we approached the ridge, I realized that the trail would not connect to the gravel road until much later, bypassing King Philip’s Cave. With the help of AllTrails we followed a short, unmarked trail that took us to the gravel road and from there we followed the same route as before as far as the Heublein Tower. From the tower we retraced our path to the junction with the blue Metacomet Trail heading north over a summit that is labeled King Philip Mountain on AllTrails, probably another place he never was. We followed this back to the parking lot.

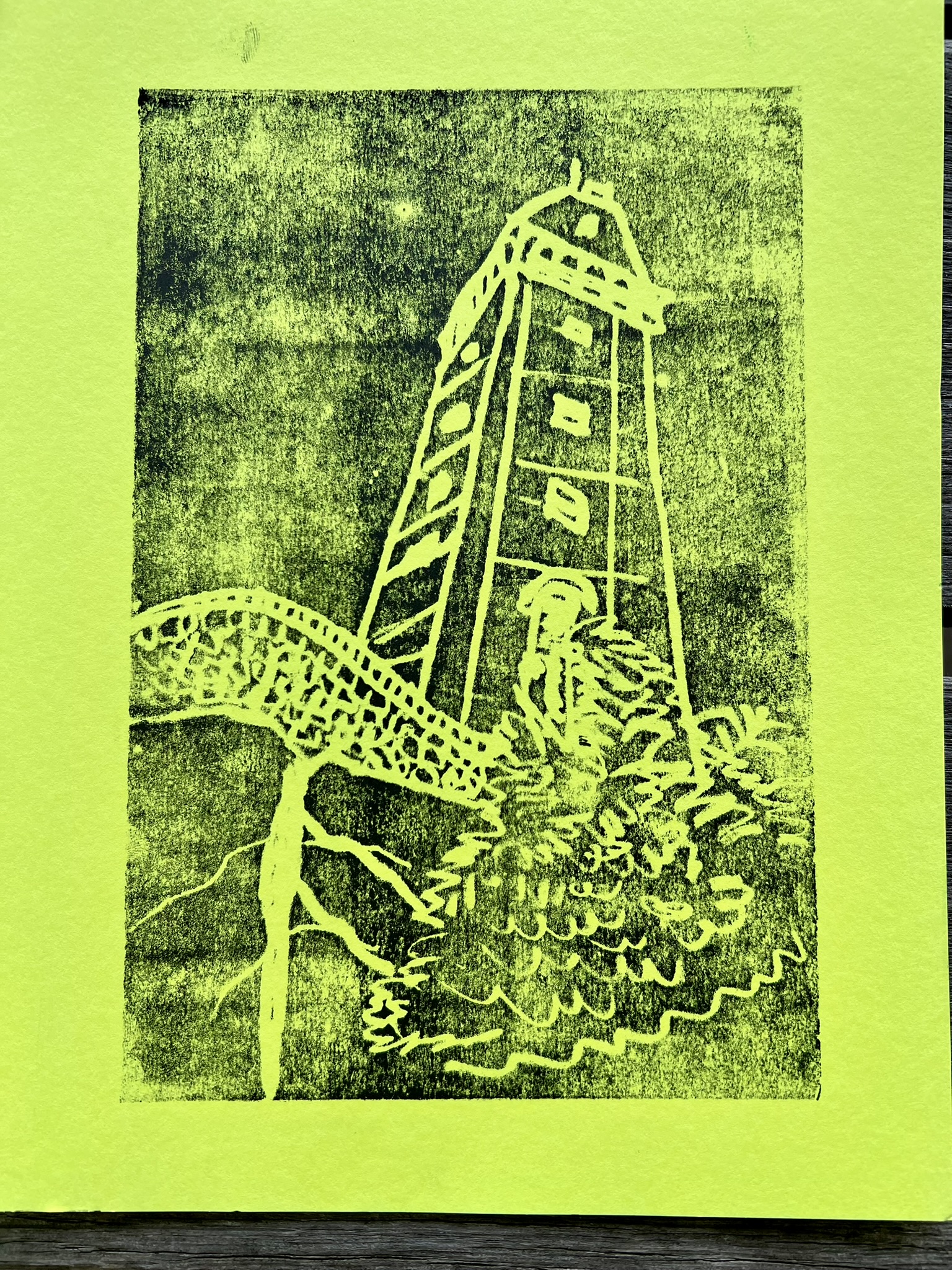

I returned once more in August for a CFPA hike with the NET’s Artist in Residence, Sam Swap. We hiked the blue Metacomet Trail to the tower and I probably bored Sam to tears with a full accounting of King Philip’s War as we hiked. Our group settled into the picnic pavilion at the summit and did a printmaking project en plein air using Styrofoam sheets and pencils. It was so much fun! Sam hopes to lead some other free art hikes in September along the NET (and possibly a section of the Metacomet Trail) so I encourage you to check the CFPA Events page and join in the fun.

From left to right: The Metacomet Trail traversing King Philip Mountain; an imposing chunk of trap rock; view of the tower from the trail below; fun with printmaking

Penwood State Park, Bloomfield. 5 miles +/-

Penwood is an 800 acre state park just north of Talcott Mountain State Park. According to the state park website, Curtis H. Veeder, an industrialist, inventor, and outdoorsman, gifted the land to the citizens of Connecticut in 1944, wishing only that his beloved hilltop “be kept in a natural state so that those who love nature may enjoy this property as I have enjoyed it.” Click HERE for the Trail Map. We chose to do a loop trail labeled in AllTrails as the Penwood State Park Yellow to Blue Loop. AllTrails lists it as 4.5 miles, but I recorded 5.2. We parked in the lot by Route 185 and did the hike counterclockwise, first walking north along the paved road until we saw the turnoff for the blue blazed Metacomet Trail. The trail heads steeply uphill, but once we reached the top of the ridge, the trail undulated up and down. After a couple of miles we came to the junction with the loop road at Lake Louise. We stopped for a snack at the picnic table, and explored the boardwalk overlooking the small lake. As this is another moderate hike with lots of rocks and roots, an alternative is to walk the loop road, which is closed to traffic after the first mile. Further north we came to the first scenic viewpoint, which was a lovely bald with views to the west over Simsbury.

From left to right: the start of the Metacomet Trail off the paved road; boardwalk at Lake Louise; CFPA built steps; ridgeline view

A little further north we took a cross-trail on the left to connect with the orange trail. This shows on the official trail map as the blue/red trail but it does not get much use and most of the blazes have faded away. The start of the trail is NOT obvious – we went right past it and had to backtrack, using the AllTrails GPS signal to pinpoint the trail. It is steep to start, but not long. When you reach a junction, turn left onto the orange trail. This trail becomes the yellow trail after crossing Lucy Brook (which feeds Lake Louise). Keep heading south on yellow. You will see a blue blazed trail on the right – this is NOT a CFPA blue-blazed trail, but a connector trail that appears to lead down to the Simsbury Land Trust’s Tanager Hill and Ellsworth properties. We stayed on yellow, which traverses the western edge of the ridge and should have good views through the trees once the leaves are down. We came to another scenic lookout with an old picnic table where we could enjoy yet another snack in the shade before returning to our car. There are options for shorter or longer hikes here.

From left to right: a section of ridgeline path; a faded blaze along the blue/red trail; viewpoint with a dilapidated picnic table; tree along the cliff edge

Bibliography

Books

King Philip’s War: The History and Legacy of American’s Forgotten Conflict, by Eric B. Schultz and Michael J. Tougias (1999)

Uncas: First of the Mohegans, by Michael Leroy Oberg (2003)

The Name of War: King Philip’s War and the Origins of American Identity, by Jill Lepore (1999)

The Wars of the Lord: The Puritan Conquest of America’s First People, by Matthew J. Tuininga (2025)

Our Beloved Kin: A New History of King Philip’s War, by Lisa Brooks (2018)

Podcasts

https://thehistoryoftheamericans.com/ 9 episodes on King Philip’s War starting with Episode 181. The goal of the podcast is as follows: “The Story of the American People: We are telling the history of the lands now encompassed by the United States, from the beginning, without (intentional) presentism. We believe there is dignity in our national story, along with tragedy, triumph, brilliance, hypocrisy, magnificence, depravity, corruption, venality, inspiration, oppression, genius, defeat, and glory.”

Inward Empire: Sword of the Wilderness (Part Two). This is the Spotify Link. Also available in Apple Podcasts. https://open.spotify.com/episode/45Dps4A3rwnpXqeDFJrCyd

Other Resources

For a Deeper Dive, following are resources about the war that are not directly included in my blog post, including a few places where King Philip might have actually been.

A Relation of the Indian War, by Rhode Island Deputy Governor, John Easton. (1675). This contemporary account of the meeting between Easton and King Philip just prior to the war is one of the best insights into the events preceding the conflict. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1036&context=libraryscience

The Search for the Site of the Great Swamp Massacre. This site includes a brief history of the war and information about different sites in Rhode Island http://smallstatebighistory.com/the-search-for-the-site-of-the-great-swamp-massacre/

Battlefields of King Phillip’s War on the Pequot Museum website https://www.kpwar.org/sample-page/memory-legacy/

This website has a succinct chronology of the war, along with excerpts from several books highlighting some of the war’s battles. https://www.forttours.com/pages/kingphilips.asp

Thorough review of archaeological dig sponsored by the Battlefield Protection Program https://www.montague-ma.gov/files/Battle_of_Turners_Falls_Project_Overview.pdf

King Philip’s Hill Trail in Northfield MA. Trail info: https://northfieldmasstrails.org/king-philips-hill/

Info about King Philip Woods Conservation Land in Sudbury. “None of the garrison houses remain today, but the foundation of the Haynes Garrison House can be seen on the adjacent town-owned parcel.” https://sudbury.ma.us/locations/kingphilip/

Local Geography and King Philip’s War. Resources for CT teachers https://teachitct.org/lessons/local-geography-and-king-philips-war/

Indian Rock – supposedly the site of a fatal skirmish during King Philip’s War https://02038.com/2008/12/indian-rock-franklin-ma/

King Philip’s Stockade in Springfield https://www.longmeadowhistoricalsociety.org/post/king-philip-s-stockade and the full Forest Park map https://www.springfield-ma.gov/park/fileadmin/Sydney/Forest_Park_Map_2024.pdf

AMC Outdoors Bulletin March 2024. Indigenous Voices on the New England Trail https://www.outdoors.org/resources/amc-outdoors/history/indigenous-voices-on-the-new-england-trail/

The New England Trail https://newenglandtrail.org/

Subscribe to Trail Talk

your next adventure awaits

Questions? Email me at naturenerdsramble@gmail.com or find me on Instagram @the_real_nature_renee.