I tumbled down another rabbit hole – this time going back almost 400 years to the Pequot War, and it all began with a glance at Google Maps looking for swaths of green.

I clicked on Fort Saybrook Monument Park, which described a “17-acre park with storyboards depicting the history of Saybrook Colony, a boardwalk & bird watching.” Intrigued, I went to visit, and while there, I noticed a reference to a FREE MAP offering a “Self-guided tour of Pequot War historical resources throughout Old Saybrook, Connecticut.” Now that sounded interesting! I stopped by the Old Saybrook Historical Society to pick up a copy, and was off and running – or in this case – walking.

In 2012 the Mashantucket Pequot Museum & Research Center enlisted the support of the Old Saybrook Historical Society, and together they applied for a grant from the United States Park Service’s American Battlefield Protection Program to locate the site of the first Fort Saybrook, which burned to the ground in 1647 and was an important site during the Pequot War of 1636-37. As I delved further, I expanded my explorations to Wethersfield (the site of an ambush during the war), and to the North Stonington/Groton area where the Pequot lived (and still live today) and where the Mistick Massacre occurred near the end of the war – another important archaeological site investigated as part of the Battlefield Protection Program.

Before I share some recommended walks and hikes, I’ll start with an abbreviated history of the Pequot War. The materials I relied on for understanding and retelling a brief history of the Pequot War are listed in my Bibliography. The publication I relied on the most was a short but informative book entitled “On the Edge of Uncertainly: The Siege and Battles of Saybrook Fort during the Pequot War. 1636-1637.” I highly recommend taking a deeper dive.

In the 1620’s, the Dutch were the primary European presence in the area and their focus was trade. In the region that is now Connecticut (an Algonquian word meaning long, tidal river), the Pequot dominated the trade relationship and were keen on keeping that privilege. In 1632, the Dutch established a trading post in present-day Hartford called the House of Hope and signed a “peace and trade” treaty with the Pequot intended to allow other tribes the opportunity to trade. However, the Pequot were reluctant to relinquish their control.

The English first arrived in 1620 in the form of a group of religious separatists, who we call the Pilgrims. They landed on the shores of Massachusetts and established the Plimoth Colony in what is now the town of Plymouth. Also in 1620, King James IV of England signed “The Great Patent of New England”, granting land rights in the “New World” to several nobles. The Earl of Warwick, Robert Rich, thought to be one of the patent holders, supposedly gave a sub-grant in 1632 to several “patentees” for a swath of land that encompassed much of the Connecticut River Valley down to present day Old Saybrook.

After King Charles I succeeded his father, King James IV, to the throne in 1625, England was thrown into political and religious turmoil that eventually led to the English Civil War. This spurred other groups to abandon England for the New World, starting with the first wave of Puritans who arrived in 1630 and established the Massachusetts Bay Colony (MBC). As the years progressed, both the MBC and Plimoth Colony were eager to compete with the Dutch in trade in the Connecticut River Valley. Plimoth Colony sent a group to build a settlement in what is now Windsor in 1633, and the MBC followed with settlements in what are now Wethersfield (1634) and Hartford (1635). These settlers were mostly welcomed by the local River Bands, at least at first, who saw an opportunity for alliances that could offer protection from the dominant Pequot.

Meanwhile, the patentees for that parcel of land that included present day Old Saybrook appointed John Winthrop, Jr. as Governor, and requested he send a work party in 1635 to what is now Saybrook Point to claim the land and start building structures in anticipation of the arrival of “Men of Qualitie” at a later date. Lion Gardiner, a Scotsman and Engineer who was hired to direct the building of a fort, arrived in April of 1636,

A few key events fueled the brewing conflict between the Europeans and the Native Americans. It is important to pause here and stress that there was no unifying governance amongst either group. On the European side, even amongst the English, there were different governing bodies such as the Plimoth Colony, Massachusetts Bay Colony and the Connecticut Colony (established in 1636). Amongst the Native Americans there were different groups or “confederacies” (such as the Pequot, Mohegan and Narragansett) that were comprised of different bands of Algonquian language speaking peoples. These bands had a history of both cooperation and rivalry that pre-dated the arrival of the first Europeans. Their relationships continued to morph afterwards, especially with the introduction of European trade goods and the arrival of European diseases that largely decimated the native population. They had complicated tributary relationships that spurred subjugated bands to seek alliances with the Europeans and with each other.

While the Pequot had agreed to allow other tribes to trade, in a display of power, Pequot warriors descended on a group of Narragansetts on a trading trip to the House of Hope in 1633 and murdered them. That did not sit well with the Dutch.

To teach the Pequot a lesson, when the Chief Sachem of the Pequot, Tatobem, later boarded a Dutch vessel to trade, he was held hostage and the Pequot were told they would only get their Chief back if they paid a certain ransom. Exhibiting some devious wordplay, after the ransom had been paid the Dutch kept their word and returned the Chief – by handing over his lifeless body.

As you can imagine, the Pequot were enraged. Following their custom along the lines of “an eye for an eye”, they sought their revenge, which they got early in 1634 after the Captain of a merchant sailing vessel kidnapped two Western Niantic men (Pequot tributaries) to act as guides. A group of Pequot warriors managed to board the vessel and murder the Captain and his crew. The problem was, the ship’s captain was not Dutch, but an English privateer named John Stone. As you can imagine, THAT did not sit well with the English!

Later in 1634, a delegation of Pequot traveled to Boston to offer a treaty of peace and trade with the MBC and give their explanation for the events that occurred. As part of the deal, the MBC wanted the killers of Captain Stone. While the Pequot agreed to comply, over the next two years they neglected to fulfill this part of the agreement.

Relations continued to worsen between the Pequot and the English, and the situation was exacerbated by the Mohegan sachem, Uncas, habitually whispering rumors in the ears of his English friends that the Pequot were planning to start a war. At the time, the Mohegan tribe was a tributary of the Pequot, and Uncas often lived in exile for rebelling against Pequot authority. Events worsened in 1636 with an incident on Block Island, the home of the Manisses band. The Wethersfield trader, John Oldham, was killed and the Pequot were blamed (Both the Pequot and Narragansett sought to control the Block Island Manisses). In retaliation, the MBC sent a contingent under the command of John Underhill to attack the Manisses. The Manisses hid in the island swamps and the English troops resorted to burning their village. Afterwards, the troops stopped at Fort Saybrook. While there, they told Lion Gardiner that they planned to continue to the Pequot village to once again demand the killers of John Stone. This frustrated Gardiner, who feared he and his men would become pawns in the fighting between the English troops of the MBC and the Pequot. His fears were justified – the Pequot decided to lay siege to the still uncompleted Saybrook Fort starting in October of 1636 – a siege that lasted seven months, into the spring of 1637. Then on April 23, 1637 in Wethersfield, Pequot warriors ambushed settlers, killing nine and kidnapping the two young daughters of William Swaine (the girls were later returned with the help of the Dutch). This triggered a declaration of war from the newly formed Connecticut Colony, with a call to arms going out to the communities of Hartford, Windsor and Wethersfield.

Together with help from the MBC and the Mohegan and Narragansett tribes, a plan of attack was devised to attack the Pequot under the cover of night. The attackers invaded the Pequot Fort at Mistick where hundreds of Pequot, including women and children, were burned in their wigwams or killed attempting to flee. This incident came to be called the Mistick Massacre. As the English retreated they were briefly pursued by Pequot warriors from a second nearby fort, but this day essentially marked the turning point of the war. Surviving Pequot attempted to flee west, but the English pursued them with an eye toward genocide. The war culminated in a final Swamp Fight in what is now Fairfield. The last survivors were either killed, sold into slavery in the West Indies, or “adopted” into the Mohegan and Narragansett tribes. But this did not mark the end of the Pequots’ story. It took almost 400 years, but the few survivors clung to their cultural traditions and stories as best they could. Later in the 1600’s both the Western Mashantucket Pequot (the ones living with the Mohegan Tribe) and Eastern Pequot (living with the Narragansett Tribe) were granted their own reservation land. The Mashantucket Pequot were granted federal recognition in 1983 and are flourishing, owning and operating the Foxwoods Casino. The Eastern Pequot were initially granted federal recognition in 2002, but this was revoked in 2005. For a much fuller look at the history of the Pequot Nation I highly recommend a visit to the Mashantucket Pequot Museum & Research Center. Admission is not inexpensive ($25 per adult ticket) but several libraries offer museum pass options. Check with your local library for details. Please note: THE MUSEUM IS CLOSED FOR RENOVATIONS AND EXPECTS TO RE-OPEN APRIL 3, 2024. Check their website HERE before making plans.

EXTENDED BATTLE ROUTE LOOP, Old Saybrook. Approximately 5.75 miles.

In August of 2023 I enlisted a friend to join me on this long walk. Parking at Fort Saybrook Monument Park we did the loop in a counter-clockwise direction, first stopping at the cemetery gate to read the signs but otherwise not touring the cemetery. From there we crossed to the north side of College Street and headed west. This becomes Main Street (Rt. 154). Although not listed in the pamphlet – don’t miss the round stones and plaque in the front yard of 530 Main Street. These are the only remaining relics of a windmill built by Lion Gardiner in 1636-37 which stood on that site for 175 years. Farther along, near 500 Main Street, look for the signboard that details the events of February 22, 1637 at Saybrook Neck, where a group of Pequot warriors ambushed Gardiner and some of his men as they were cutting reeds. From here, take a left onto Maple Avenue. As Maple Avenue turns the corner, take Hartland Drive on your right and follow it to Cornfield Point. This point got its name from the acres of corn that were planted there to supply the fort. Why the fields were planted so far from the fort is lost to history, but the pamphlet suggests that the land had previously been “cleared by the Western Niantic Indians who lived in the area and recently sold their land to John Winthrop, Jr. and Saybrook Colony”. There is a signboard with information and several benches at the scenic overlook where you can rest and admire the view. From Cornfield Point head back to Maple Avenue via Sea Lane and turn right, walking along the waterfront. We did not locate a signboard for Guardhouse Point – but the old guardhouse was generally in the area of the Knollwood Beach sign and its significance is described in the pamphlet. Continuing along, Maple Avenue becomes Bridge Street as you near the causeway. Stop at the causeway to read about South Cove and try to envision the English soldiers crossing the cove in canoes to get to their cornfields before there was a bridge connecting the points of land. From there continue on Bridge Street until you reach College Street, then turn left and head back to Fort Saybrook Monument Park. From here you can do the Fort Siege Route or, like we did, save that for another day. (SIDE NOTE: It was on this walk just before reaching the causeway that I discovered the trailhead to the Fenwick Grove Trail featured in my January 2024 Sunrise Adventures blog post. You can add this wooded loop trail to your walk for an additional .7 miles).

from left to right: the mill wheel and dedication sign along Main Street; the storyboard and contemplation benches at Cornfield Point

FORT SIEGE ROUTE LOOP, Old Saybrook. Approximately 2.5 miles.

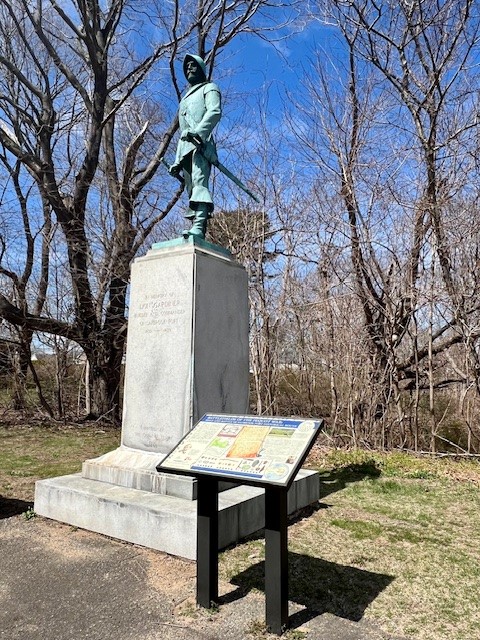

On a mild December morning my friend and I regrouped to walk the loop encompassing North Cove, Fort Saybrook Monument Park and Gardiner’s Point. Starting at Fort Saybrook we headed west on College Street and took a right onto North Cove. Going in a clockwise direction we passed the Town Boat Launch where there is a bench overlooking the cove. Further along look for the public access pathway marked by a wooden barrier and a “Scenic Overlook” sign. From the street take a close look at the white house to the left of the path. This is the former Black Horse Tavern built c. 1712. Follow the path to the edge of the water and enjoy the views of North Cove. It is thought that the Saybrook Fort Warehouse and Wharf from the 17th century was located in this general vicinity. From there we toured Fort Saybrook. As the pamphlet explains, the park “was dedicated in 1985 on what was at the time thought to be the approximate site” of the original Saybrook Fort. The archaeological work that was done as part of the grant program helped to identify the actual location of the fort, which can be seen from the viewing platform by the marsh. Along with the viewing platform, there are signboards erected around the park with information about the forts, the Pequot War, and the flora and fauna of the area. There is also a statue of Lion Gardiner that his descendants erected in 1930, and the remains of the Connecticut Valley Railroad Roundhouse that was built in 1871. From there it is a short walk to Gardiner’s Landing, a small park that offers sweeping views of the Connecticut River as it flows into Long Island Sound. The fort burned down in 1647 and a new fort, called Fort Fenwick, was erected on a hill at this spot. According to the pamphlet, “the fort site was demolished….in 1871 and the hill was used to build the railroad beds across North and South Cove.”

from left to right: path to the North Cove scenic overlook; Driftwood at the overlook; viewing platform at the park and storyboard indicating the site of the original fort on the distant hill

from left to right: Fort Saybrook Monument Park; the Lion Gardiner statue; the remains of the railroad roundhouse constructed in 1871; Gardiner’s Landing

After our walk, I drove to the Baldwin Bridge State Boat Launch. This is the general site of Warehouse Point (#12 on the map) where, according to the pamphlet, there were “warehouses built by English traders who lived upriver in the towns of Wethersfield, Hartford and Windsor as a convenient location to store goods.” When Lt. Gardiner determined he could not effectively protect the warehouses, he ordered their contents to be transferred to the fort. The very next day the warehouses were destroyed. You can walk out onto the fishing pier for views up and down the river and imagine what it might have looked like 400 years ago.

Views of the Connecticut River from the Baldwin Bridge State Boat Launch

After soaking up some history in Old Saybrook, it was time to venture east to the ancestral Pequot lands in the area of present day North Stonington and Groton. I visited three trails on the last day of January. The two Groton trails are near where the old Mistick Fort was believed to be.

LANTERN HILL, North Stonington. 1.5 miles with 318’ of ascent.

Lantern Hill marks the southwest terminus of the blue-blazed Narragansett Trail maintained by the Connecticut Forest & Park Association. I chose a short loop trail which combined the blue trail with a trail built and maintained by the Mashuntucket Pequot Tribal Nation. The first part of the trail is a rocky road bed that can be quite muddy. Hikers have worn a trail on the left side bank that is drier. I took this on the way down and noticed what seemed to be a shrine of sorts with a face seemingly carved out of a burl that I missed on the way up. At the first junction I stayed left and followed the blue trail. At this point the trail becomes much more interesting as you make your way up the rocky outcroppings. There are many pretty scrub pines and several places where you can get a good view of Lantern Hill Pond and the Foxwoods Casino below. As you near the top there is a ledge on the left with a magnificent view to the east.

from left to right: A carving attached to a tree to left of trail; pine trees; a typical ledge section; overlook facing to the east

Coming down there are some challenging boulder scrambles. After a short descent, instead of continuing on blue, take the well-worn unmarked trail that goes straight. After a short distance there is a spur trail that leads to the best view overlooking Lantern Hill Pond. Retrace your steps and continue on the unmarked trail until you come to a T intersection. Turn right. This trail was originally marked with the red arrow blazes of the Foxwoods Resort, but many of the blazes are no longer visible. Cut into the side of the steep quartz hill, this trail goes along the cliff face. It eventually meets the blue trail and descends to the parking area. The parking is a wide pullout along the road with room for several cars. While there are no facilities, the Boy Scouts provide a single trash receptacle at the trailhead. I used this AllTrails map as a guide. This map does not consistently follow blue. I stuck to the blue trail which I believe is probably more scenic.

from left to right: Lantern Hill Pond; the blue-blazed trail down; the trail cut into the quartz cliff face; tumbled boulders line the trail.

PEQUOT WOODS, Groton. Approximately 3 miles with 234’ of ascent.

There is a parking pullout at the trailhead with room for several cars. I did the blue loop counterclockwise, starting by going alongside Billings Pond. The pond looked like the perfect habitat for frog and bird watching and I made a mental note to return in the spring. There are a few benches along the pond’s edge and what looks like a beaver deceiver. The trail at first is an old woods road running alongside a stone wall. There are lots of very muddy spots but all were maneuverable with careful rock-hopping. As the trails starts to curve around there are more classic glacial boulders. A footbridge crosses Fishtown Brook. While you can cut straight across to start your loop back, I recommend following blue to the right as it skirts the edge of the marsh.

from left to right: Billings Pond; a “beaver deceiver” at the pond outlet; the trails can flood in wet weather but rock-hopping is possible; the footbridge over Fishtown Brook

When it finally loops around you will briefly pop out onto the edge of a home’s backyard. Once you do this, look left and you will see where the trail reenters the woods. At this point the topography is a glacial jumble which adds some nice variety to the hike. There is a yellow loop you can take. While I followed the yellow blazes, they brought me back to the blue trail sooner than I expected, so I am wondering if the yellow trail has more than one branch. The rest of the blue trail gets easier to follow, more like the woods road at the beginning. There is also red trail cutover to create a shorter hike that avoids the worst of the rock-hopping. There is a trail map posted at the trailhead, but I could not find it online. For an idea of the trails without showing the blaze colors, see this AllTrails map.

from left to right: another challenging trail section; one of many glacial boulders dotting the landscape; some sections of trail were easier to navigate; Dedication boulder

PEACE SANCTUARY, Groton. 1 mile with 155’ of ascent.

This parcel is owned by the Mary L. Jobe Akeley Trust and stewarded by the Denison Pequotsepos Nature Center. There is a pullout for parking on River Road just past the chained driveway and sign. After entering the drive, I took the first unmarked trail to the left, starting my walk in a clockwise loop. The trail climbed a short distance to a fence and stone seat looking out over the Mystic River to Mystic Seaport. Continuing on, I reached an open area that seemed like an old garden with a water pump and strategically placed rocks. I continued through a break in the stone wall. At one point I observed the crumbled foundation of an old building. When in doubt I just stayed to the left. The trail generally followed the perimeter of the sanctuary, and I used AllTrails to judge where I was on the parcel, even though the specific trails aren’t shown. I eventually popped out on the driveway near the top and noticed a trail sign that said “Private Nature Preserve – Access by current DPNC members and by permission only”. I found this to be at odds with the information on the website, which I double-checked afterwards and which clearly states that the trails are open free to the public from dawn to dusk. I choose to believe that the website is the most up-to-date. Following the driveway back down, I stopped to look at the old cisterns surrounded by protective fencing. Dogs are permitted on leash. For more information, visit their website HERE.

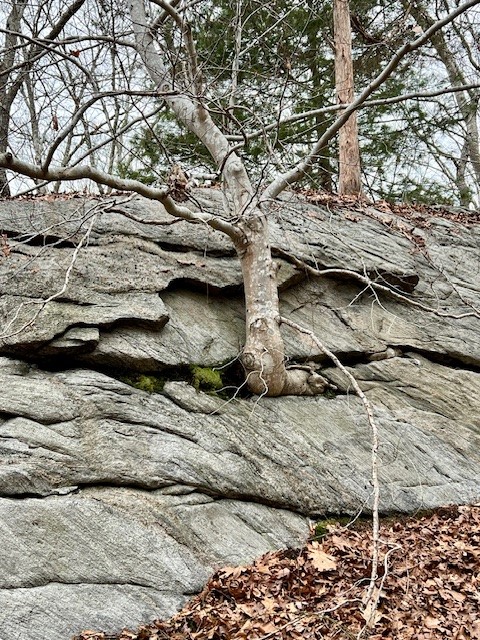

from left to right: View of the Mystic River; what appeared to be an old garden area; a determined tree along the trail; the sign I encountered at the end of my walk

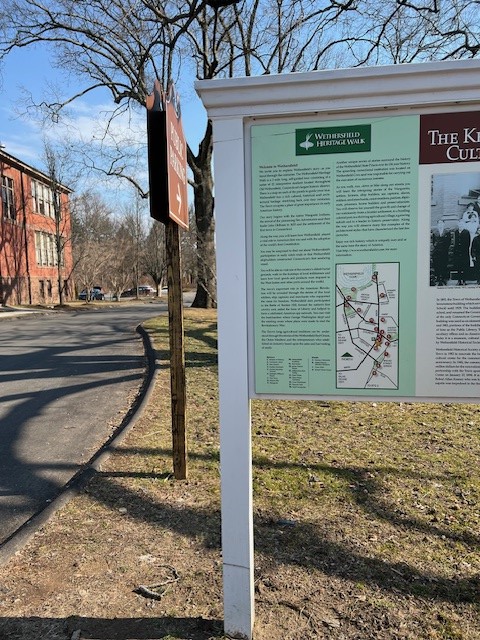

My final destination before emerging from this rabbit hole was the town of Wethersfield, which I learned had published a brochure and map for a 3 mile Heritage Walk featuring 22 points of interest highlighting the town’s history. I chose to create my own walking routes centered on my interest in the Pequot War. I will share my routes, but recommend extending your visit to include any of the sites that interest you. With a promise of lunch and an afternoon latte I convinced my husband, Tom, to join me on this adventure. You can find a link to the map HERE. For cyclists, there is a recommended 8 mile bike route called the Heritage Walk Bikeway Path. You can find that map HERE .

COVE PATH, Wethersfield. One mile out and back.

We started at Cove Park on Hartford Avenue and walked across the open field that formerly housed a State Prison to get to the walking path. Along the way there is a marker (#15) by the old prison cemetery. The walking path winds along the edge of Wethersfield Cove. There are several benches and picnic tables along the path, which eventually leads to the Cove Warehouse and a new fishing dock. Marker #16 explains that “the warehouse was located at a strategic bend on the bank of the Connecticut River” and that “in 1692, a flood moved the course of the river to the east and swept away all but this one remaining warehouse.” (Note: the Cove Warehouse website dates the flood to 1697.) Although the warehouses were built a few decades after the Pequot War, this knowledge gave me an appreciation for why John Oldman and the “Ten Adventurers” chose this spot for their settlement. It was an unseasonably warm day for late February, and many folks were out walking and trying their luck fishing on what appeared to be a fairly new pier. There is a parking lot at the Cove Warehouse and Boat Launch section of Cove Park, so there is an option to do the walk in reverse or to just visit the cove and warehouse eliminating the walk altogether. According to the WEBSITE, The Cove Warehouse is open Saturdays and Sundays, 1:00 pm – 4:00 pm, late May through early October. Admission is free, but donations are gratefully accepted.

We returned to our car and drove to Main Street downtown Old Wethersfield for our lunch interlude. This is where my plans went awry. My chosen lunch place was temporarily closed for renovations and my chosen afternoon latte spot was also closed. Uh-oh! I would need to pivot fast or break my promise, and I was reluctant to do the latter. Fortunately, I saw that Lucky Lou’s Bar & Grill across the street was open, and we were able to have a tasty lunch before our afternoon walk.

DOWNTOWN LOOP, Wethersfield. 1.3 miles.

Leaving Lucky Lou’s, we embarked on a counter clockwise loop, heading south on Main Street. We stopped to read the markers at the Keeney Memorial Center (which houses the Wethersfield Museum), the Hurlbut Dunham House, and the Old Academy. Both the Keeney Center and the Hurlbut Dunham house are open to the public, and visiting information can be found HERE. Across the street is the Webb-Deane-Stevens Museum which was closed for the season but should reopen on May 1. Check the museum website HERE for details.

We took a left on Garden Street, proceeding to the Broad Street Green. Making our way to the southeast quadrant of the green, we found the two markers with information about the Pequot War (#9) and the Wangunk (#8). The word Wangunk means “the people at the bend in the river”, and according to the marker, they had a village they called Pyquag which would later become Wethersfield. They were a farming community, supplemented by hunting and gathering and were one of the groups decimated by smallpox that had become subservient to the more powerful Pequot. From there we walked north on Broad Street to the intersection with Church Street. Don’t miss the Buttolph-Williams House at the corner of Broad and Church. This early 1700’s house inspired the setting for Elizabeth George Speare’s young adult novel, The Witch of Blackbird Pond. We toured this house many years ago, one of the highlights while chaperoning middle school field trips that I remember fondly and that my kids barely remember. We turned left to head back to our car, but I recommend crossing the street and walking around the Ancient Burying Ground (another stop on that middle school field trip). According to the Heritage Walk brochure this is one of Connecticut’s oldest burying grounds and is a site on the Connecticut Freedom Trail. We had parked on Main Street in front of the Heirloom Market, which serendipitously served a delicious latte. This market offers another choice for a lunch spot, in addition to selling heirloom seeds of all kinds.

from left to right: An introduction to the Heritage Walk outside the Keeney Memorial Center; the Broad Street Green; the Buttolph-Williams House

WINTERGREEN WOODS, Wethersfield. Just under 1 mile.

I had one additional stop in mind before heading home – a short woods walk nearby in a place called Wintergreen Woods. Although this spot has nothing to do with the Pequot War, I offer it up as a brief nature respite to round out the day. We parked in the lot at the end of Folly Brook Boulevard. This is also a parking spot for the Heritage Bikeway Path. From the parking area the entrance to the walking path is at the woods to the left. There is a loop that winds its way past numerous vernal pools with several boardwalks over the muddiest sections. There is also a small pond with a new bridge that was a CCSU (Central Connecticut State University) Civil Engineering Project. The topography that allowed the vernal pools was interesting. I did some research later and learned that these depressions were formed during the last glacial period. For a complete history of Wintergreen Woods click HERE.

from left to right: The Bike Path; the walking path is through a flat woodlands pockmarked by vernal pool depressions; a section of boardwalk; new bridge over Folly Brook by the pond

BIBLIOGRAPHY

The following hard copy materials I found at the Killingworth Library or through its inter-library loan program:

- On the Edge of Uncertainly: The Siege and Battles of Saybrook Fort during the Pequot War. 1636-1637, by James T. Powers. 2020, Old Saybrook Historical Society.

- The History Channel Presents: 10 Days that Unexpectedly Changed America. Episode 1: Massacre at Mystic. DVD (2006)

- Uncas: First of the Mohegans, by Michael Leroy Oberg. (2003)

- A History of Mystic Connecticut: From Pequot Village to Tourist Town, by Leigh Fought (2007)

Inward Empire (Podcast – 14 episodes). Episode 1: Sword of the Wilderness, Part I (2/10/2015. 2h 44m). Long but very well-done podcast.

A 2010 article about the archaeological work conducted in Mystic as part of the Pequot War battlefield discovery project. Link HERE.

Post from the blog “Today in Connecticut History” (from the office of the State Historian and the CT Humanities) about the Wethersfield attack. Link HERE.

Article entitled “Exploring and Uncovering the Pequot War”, from the Connecticut Explored website, the “magazine and podcast of Connecticut history”.

Also from Connecticut Explored: “Remembering the Pequot War in Fairfield”.

The official website of the Pequot War, sponsored by the Mashantucket Pequot Museum & Science Center and the American Battlefield Protection Program https://pequotwar.org/

- Information about the Battle of Mistick Fort http://pequotwar.org/archaeology/overviewbattle-of-mistic-fort/

- Information about the Siege on Fort Saybrook https://pequotwar.org/archaeology/overview-siege-and-battle-of-saybrook-fort/

“This Hard Land: The Eastern Pequots struggle to reclaim tribal territory” published in Connecticut College Magazine, Winter 2020.

Once Upon a Time in Connecticut, by Caroline Clifford Newton. This 140 page book, published in 1916, is available to read in its entirety online HERE. I like to think that our awareness of how history is portrayed has become more nuanced over time, so I am always interested to see how events are described in another era. The chapter entitled “The Fort on the River” recounts the story of the Saybrook Fort at the time of the Pequot War.

Subscribe to Trail Talk

your next adventure awaits

Questions? Email me at naturenerdsramble@gmail.com or find me on Instagram @the_real_nature_renee.